I’m 63 now, so the idea that I should still be taking part in “adventure sports” is perhaps a little ridiculous. Nonetheless, rock climbing has been so much part of my life for so long that I still try and get out, generally for easy short climbs on the gritstone cliffs near my home in Derbyshire. There are things that I’ve done in my younger days that I have put behind me without much regret – I won’t be climbing frozen waterfalls in New England again, or winter climbing in the Lakes or Scotland. I do miss snowy mountains a bit, though I know I will never be a serious alpinist. But there’s one variety of cllmbing that I think is very special, that I look back on with real pleasure, and that I think maybe I should try to involve myself in once again, even if at a much lower level than before. That is rock climbing on Britain’s sea-cliffs, a branch of the pastime with its own unique atmosphere and set of demands.

I started rock climbing seriously when I was 14 or so; at that time it was my family’s habit to spend every summer in St Davids, Pembrokeshire, near where my mother had grown up. The coastline of Pembrokeshire is spectacular – a succession of coves, headlands, and cliffs, pounded by the open Atlantic waves. At the time, the idea of climbing the cliffs of Pembrokeshire was in its infancy. Rock climbing on the granite cliffs of Cornwall was well-established, and the counter-cultural climbing scene of North Wales had created hard and serious routes on the sea-cliffs of Gogarth, on Anglesea. But what little climbing on the cliffs of Pembrokeshire was recorded in a slim guidebook by Colin Mortlock, published in 1974, not by the Climbers Club or any of the establishment sources of climbing information, but by a local publishing house more associated with postcards and wildlife guides than rock climbing.

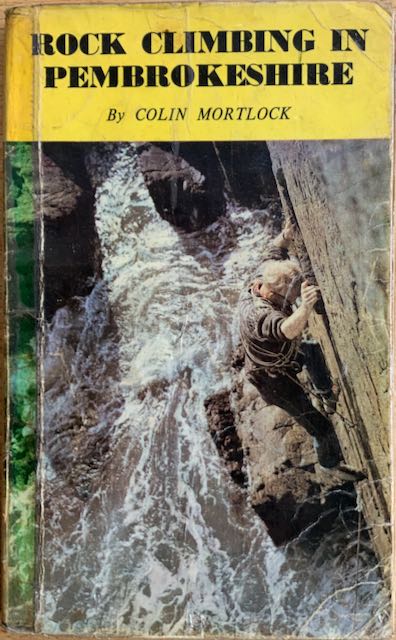

The first ever guidebook to climbing in Pembrokeshire, by Colin Mortlock. Just 150 pages long (the current guidebook runs to 5 volumes), it often failed in the basic function of telling one where the routes go (and, in one or two cases, even where the cliffs actually are), but was a source of great inspiration. The cover photograph is of Colin Mortlock himself climbing “Red Wall” at Porthclais.

My imagination was seized by the cover of this book, showing Mortlock himself powering up a sheer, apparently overhanging, wall above a boiling sea. The route was called “Red Wall”, and was graded “severe” – that was the kind of climbing I wanted to do. In 1977 I persuaded my school friend and climbing partner Mark Miller to come and stay with my family in Pembrokeshire so we could give this sea-cliff climbing business a try.

Mark and I were, by that time, reasonably confident climbers up to grades of severe, with some level of basic competence at rope work and protection, and in possession of the basic gear – ropes, harnesses, the nuts and slings that were state of the art at the time. We studied the guidebook and looked at the picture. It looked steep – but surely, if it were that overhanging, the holds must be good. We’d done routes like that on the gritstone cliffs of Derbyshire, we thought – tough routes for the grade, but within our grasp.

But we’d misjudged it. The cover picture turned out to wildly tilted; it’s an off-vertical slab, maybe 70 degrees or so, blessed with perfect sharp, incut finger holds. We romped up it. Severe? It would barely be V. Diff in the Peak District! But it remains one of my favourite routes – I’ve probably done it twenty times since then. Few routes capture so completely the joy of sea-cliff climbing at its friendliest, with easy access to the base of the route, clear blue water sloshing gently below one’s feet, lichen and rock samphire on beautiful pink rock, footholds and handholds in all the right places.

Mark and I got better and more experienced at climbing. By the time we left school I was a confident leader of climbs VS in grade, tentatively trying things that were a bit harder. Mark had by force of will converted himself into an extreme leader, with a specialism in bold, protection-less slabs. In the summer before I went to University, in 1980, we persuaded a relatively new friend, Peter Carter, to come with us to Cornwall and Devon. Or, more accurately, we persuaded Peter to take us there – recently discharged from the Royal Marines, he had the unique asset of owning, and knowing how to drive, a small van.

Our trip started at the very tip of Cornwall – on the granite cliffs of West Penwith. We did some fine climbs on the traditional cliffs of solid granite, like Bosigran and Chair Ladder. But it was on the return trip that our sea-cliff horizons were truly expanded. A bleak headland near the north coast village of St Agnes is known to climbers as Carn Gowla, with three hundred foot cliffs falling vertically into the deep sea.

The route we chose was a HVS called Mercury. The first problem is getting to the base of the route – the only way was to abseil. We tied two 150ft 9 mm ropes together, anchored them to a good thread in the slope above the groove, and set off down. At the bottom, a ledge about twenty feet above the waves, there’s a huge sense of commitment – the easiest way out is the route Mercury, all 270 ft of it. In the end, the technical difficulties weren’t beyond us, though the exposure, commitment, and the dubious, vegetated rock were very far from the friendly crags of the Peak District.

Another highlight of that trip was my first encounter with the spectacular scenery on the stretch of coast north from Bude to Hartland. Known as the Culm Coast, it’s composed of thinly bedded sandstones and shales that have been dramatically folded, and then sliced abruptly by the sea. Not only is it the most dramatic coastal scenery in England, it also provides a variety of great climbs, ranging from short and solid sea-washed slabs to 400 foot climbs, almost of mountain scale, on rock whose solidity is not above suspicion. I’ve returned to it again and again.

There’s something uniquely memorable, I think, about sea cliff climbs, and even decades on I vividly remember the climbs and the people I did with them with. On the Culm Coast there’s a 400 ft climb called Wrecker’s Slab. The first time I did it was with my college friend Jonathan Sharp, I think just a few months before he tragically died in the Alps. It wasn’t hard, but its scale and looseness gave it quite a reputation, well-deserved.

In Pembrokeshire, amongst the cliffs north of St Davids, Trwyn Llwyd is a fabulous buttress of solid gabbro. I did Barad with Sean Smith; its crux felt like a VS gritstone jamming crack – 200 feet directly above the sea. Craig Coetan is a much easier crag, above a little inlet which attracts curious seals. In my teenage years I explored these gentle slabs with my father.

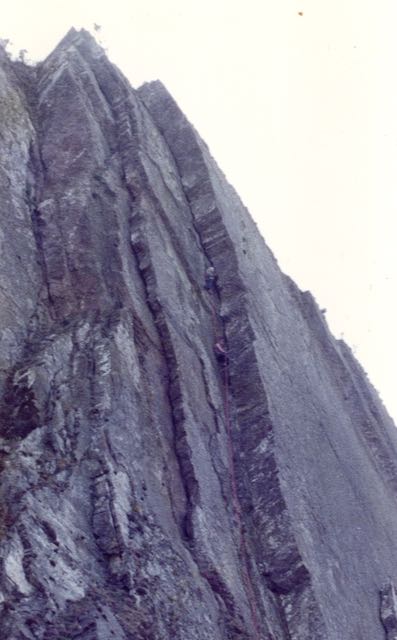

Back in the Culm coast, the hardest route I did was with my old and much missed friend, the late Mark Miller. Blackchurch is a crag with a sinister atmosphere that entirely lives up to its name; Archtempter is one of the classics of the main cliff – a soaring groove line now graded E3. Mark did the first pitch, thin and loose, and I led the widening crack above through an overhang. At the top, we so far forgot ourselves to shake hands.

Blackchurch, North Devon. The obvious groove is the line of “Archtempter”; the (just visible) climbers are Mark Miller at the halfway stance, and above him the author, just about to enter the overhanging section. It’s not a great photo, but it does convey something of the demonic atmosphere of this crag.

Looking for new routes provides another, exploratory dimension to sea-cliff climbing; I had many memorable trips with Brian Davison, who believed that the purpose of guide books was to tell you where not to climb. In the Lleyn Peninsula, we did one of the earliest routes up Craig Dorys; we called it “Error of Judgement”. As the guidebook says: “It certainly was, an appallingly loose line”.

In North Pembrokeshire Penbwchdy is a long headland with a long run of big, vegetated cliffs. I’d been there with Jonathan Sharp but failed to get up anything – we’d scrambled down a grassy slope, done a 150 ft abseil to sea level to find our way forward was to cross a deep but narrow inlet on the remains of a wrecked ship. Not relishing the idea of balancing across on an old propeller shaft, over which waves were breaking, we went back the way we came.

The great pioneer of sea-cliff climbing, Pat Littlejohn, had a done a route at the far end of Penbwchdy, on a section of cliff he called New World Wall, accessed by a long low-tide sea level traverse after the shipwreck crossing that Jonathan and I had balked at. Done in 1974, I suspect Terranova, as the route was called, hadn’t had a lot of repeats, given the awkward approach. But Brian and I later found another way down to New World Wall, with some careful route finding and a final scramble. Brian led a new route up this, which he called “New Dawn Fades”, at E4, a good onsight lead up a steep groove.

The best new route I ever did was on the sandstone cliffs south of St Davids, a couple of miles east of Porthclais. A pamphlet describing new routes reported a new crag on the headland near Caerfai, with a HVS called “Amorican”, now a classic and often repeated route. I kicked myself – I’d walked past that crag innumerable times but never noticed its potential. But to the right of the crack of Amorican is a sweeping concave slab of sandstone, unclimbed in 1984. Climbing with Mary Rack, I found a circuitous line; a thin sloping crack demanded 20 ft of intricate and precise footwork, with only tiny holds for the hands. I called it “Uncertain Smile”.

Sea cliff climbing undoubtedly has more danger than the landward variety – loose rock, tidal conditions, big waves. One experience in Cornwall was the closest I have (knowingly) come to dying. My climbing partner was José Luis Bermudez; we were staying at the Climbers Club hut at Bosigran, where I remember being hubristically superior, as experienced climbers and successful young academics, to the party of university students we were sharing the hut with.

The next day we went to Fox Promontory, a slightly obscure granite headland on the south side of the West Penwith peninsula. We scrambled down above the March seas to a sloping platform, maybe 20 feet above the level of the sea. But freak waves do exist; I remember seeing a wall of water coming towards me, then a huge weight knocking me down and dragging me downwards across the rough granite. José had been on a higher level than me, I felt him grab me as I came to a stop a few feet above the sea. We hastened to climb out, me soaking wet, nearly hypothermic by the time we got to the top of the route, with the whole of the front of my body grazed and bloody, feeling like I had been dragged across a cheese-grater.

At some point in my 30s I realised I didn’t any more have the bottle to do big serious sea-cliff routes any more. One memorable day out with Brian Davison probably confirmed this; he had his eye on an unclimbed sea-stack close to Fishguard – Needle Rock. But to get to it we had to get to the bottom of a 200 foot cliff, also unclimbed. We abseiled as far as a 150 rope would take us. We had to descend the last 50 ft using the ropes we were going to climb with, so when we got to the gap between the cliff and the needle we had to pull them down after us. Now we had to get up the sea-stack and down again before the route back to the main cliff was cut off by the tide, and then find a new route on-sight to get back up the mainland cliff.

In the end it was fine – Brian led a good route up the sea-stack, which he named “Needless to say”. And there was a relatively straightforward route up the main cliff to be found, at about VS in grade. Brian is a superbly strong and resourceful climber; there is no-one I would trust more to get out of a sticky situation, and there really was nothing to worry about, but I could feel myself losing my cool and succumbing to anxiety and fear.

I think those routes were pretty much the last serious, extreme routes I’ve done on sea-cliffs. But sea-cliff climbing doesn’t always have to be like that. There is still joy to be had in gentle routes above quiet seas. And there is no better example of that than the route I started this piece with, Red Wall at Porthclais, still one of my favourite routes anywhere.

The gentler side of sea-cliff climbing. The author on his umpteenth ascent of Red Wall, Porthclais, near St David’s; this picture gives a much more accurate sense of the character of the route than the cover picture of the Mortlock guide!